Reclaiming the Asquamchumaukee

John Stark and the Abenaki People

Listen here

John Stark is New Hampshire's greatest military hero. In this podcast you will come to learn that Stark not only had a soft spot for the Abenaki people but that soft spot may very well be the reason we live in the United States of America today and not England. Host Wayne King makes the case for respecting both the Abenaki and John Stark by restoring the name of the Asquamchumaukee River.

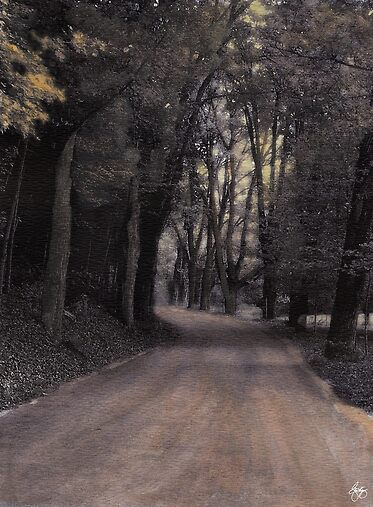

In the heart of New Hampshire, the geographic center of the state, is a beautiful meandering river that is the focal point of a very special community of people and a landscape that grows into the heart like a spreading wildfire.

The original natives of the region, at least those within the last few thousand years, the people whom we know as Abenaki, called it Asquamchumaukee. A beautiful and poetic name meaning “Place of Mountain Waters” or “place where Salmon Spawn” depending on which interpretation of the word you choose.

Flowing down from the southwestern heights of the Moosilaukee range, it is an archetype of a river flowing freely along the valley in the southern foothills of New Hampshire's White Mountains to the east of the Upper Valley Region, beginning with the fast flowing waters tumbling down from the region around Mount Moosilauke and ending in broad lugubrious oxbows where it meets the Pemigewasset River in Plymouth.

Anyone who has canoed the Baker or climbed Rattlesnake Mountain or hiked Mount Cube; anyone who has bicycled or driven along the Buffalo Road, can't help but fall in love with this area. If the landscape isn't enough the people will seal the deal: pragmatic, serious-minded in their politics, and deeply devoted to their families; people who work hard, play hard and who immerse themselves joyfully in the life of their community and the other communities of the valley.

“Asquamchumaukee. This was the name that my father's ancestors, or more accurately my great grandmother’s ancestors - my ancestors - gave to this river and the valley through which it flowed. These were people among a confederation of tribes we generally refer to as Abenaki. The Abenaki were part of a larger New England wide confederacy known as Wabanaki - “People of the Dawnland”. Today, we believe that they have lived in the state for nearly 10,000 years, perhaps longer.

Here’s Doug McLane who grew up in Manchester and now resides in Plymouth. A former Biology teacher and now a businessman in Plymouth, both Doug and his father were amateur archeologists with a particular interest in the native people of New Hampshire.

Doug McLane quote

Now Doug was speaking about a site along the Merrimack River in Manchester - a site almost 60 miles downriver from the Asquamchumaukee Valley - that was once home to the Stark family.

OK - so stay with me - we are going to bring all of this together before we are done today. But in order to tell you this tale0 and to speculate on how a very special relationship developed between the Stark family and the Abenaki people, one that may very well have extended over time, we need to go back a bit farther in time

As I said, The Asquamchumaukee Valley, ran from the Moosilaukee region to its junction with the Pemigewasset River in what is today Plymouth, New Hampshire;

The name of the river was changed after 1712 when Lieutenant Thomas Baker and a patrol of 35 rangers attacked and obliterated a peaceful village of Abenaki from a small tribal group known as the Pemigewasset. Details of the attack from records are sketchy and involve competing narratives. Oral accounts, passed down over the years among the Abenaki seem to indicate that most of the men from the village were hunting at the time of the attack and that the Indians killed were largely women and children but we know from written records that the village’s Sachem - its spiritual leader - WATERNUMMUS was among those killed and the shots that killed him came from Baker himself. We also know from other records that Baker was likely engaged in a “blood feud” of sorts with Waternummus. As a younger man he had been a leader of the Abenaki in the Deerfield Raid during the earlier French and Indian War, a raid that had captured Baker and brought him to Quebec - a prisoner of the French until he was ransomed back 2 years later.

But on the banks of the Asquamchumaukee and Pemigewasset Rivers on that fateful day Thomas Baker and his troops took no prisoners. The entire village was destroyed and the troops of Baker suffered no recorded losses. They also returned to their base in Northampton Massachusetts with a wealth of beaver and deer pelts as well as salmon, stolen from the village and what was estimated to be 20-30 scalps of the dead for which they were paid 40 pounds sterling. Thomas Baker was promoted to Captain and the river was renamed in his honor.

Other than this incident, labelled a battle by the British records and a massacre by the Abenaki, including the few Pemigewasset that remained after returning to find their village burned and their families dead, there is no public record of any heroic exploits by Thomas Baker either before of following the incident.

For all of the years that followed - right up to the present day - in spite of the official action that changed the name of the river and the valley through which it flowed, the people of this valley have preserved the Abenaki name. Even the local chapter of the vaunted Daughters of the American Revolution is known as the Asquamchumaukee Chapter. There are snowmobile clubs, shooting ranges, clubs and societies all bearing the name Asquamchumaukee - a quiet testament to those who rejected the official name change.

In 1969 when the US congress established the very first Earth Day, The valley of the Asquamchumaukee was prominently on the minds of local folks. In the early 1970s - shortly after the establishment of Earth day by Congressional action, led by a group of individuals that included the storied Senator Gaylord Nelson and a local NH environmental hero named Syd Howe, I was guiding backpacking and canoe trips in the White Mountains for Camp Mowglis, School of the Open on Newfound Lake. Every summer from 1970 to 1982 I would oversee river cleanups on both the Pemigewasset and Baker/Asquamchumaukee rivers; removing tons of debris, tires and trash each time. I was not alone. Other independent actions by environmental leaders in our communities. Dr Larry Spencer and Dr. Lisa Doner of Plymouth State University both tell of numerous cleanups on the Asquamchumaukee and Pemigewasset Rivers, with hundreds of Plymouth State students and citizens. A separate movement among local citizens, including my own parents and other local environmental leaders like Pat and Tom Schlesinger of New Hampton and Dr Larry Cushman of Rumney joined together to advocate for an end to dumping pollutants and sewage into the river by the mills and towns along their paths. These were trailblazers who took great personal risks and endured threats to their homes and their safety.

All of these activities helped reverse the terrible degradation of the rivers during the earlier years of the 20th century.

Dr Spencer

Dr. Lisa Doner

For all these reasons, it seems fitting that we ask whether justice and moral authority should compel us to examine the question of whether we should restore the original name to this beautiful river and the valley.

For thousands of years the Abenaki, and the nameless archaic tribes who preceded them, had hunted and fished these lands. Warring at times with the Iroquois, but largely living in peace and creating trading routes and favored hunting grounds, running from the boreal forests of Canada to the sea.

It would be a mistake to think that, after Columbus’s wrong turn, relations were characterized by fighting between native people and European immigrants. Though there were certainly periods of conflict, they were often a result of conflicts between warring European powers into which native people were drawn because of their ongoing relationships with one country or another.

One of the most interesting example involved a family with a very familiar name. Stark.

In 1720 Archibald Stark and his wife Eleanor embarked for America from his native Scotland in the company of many of his countrymen. The journey was long and difficult and though the ship arrived in Boston in late autumn its cargo of immigrants were not allowed to debark because many of the voyagers were ill with smallpox. Instead they were rerouted to Wiscasset, Maine where they would spend the winter and finally find their way to New Hampshire, ultimately landing in what is now Manchester.

It’s unlikely that you know the names of Archibald and Eleanor Stark but you will likely know the name of their 3rd child, John Stark, born in 1728. If not, you will certainly know his most famous quote, found on every New Hampshire license plate “Live Free or Die”. Uttered, they say, at the pivotal battle of Bennington, in the American Revolution. If it had not been for his leadership in that battle, along with 1600 New Hampshire militia men, personally recruited by Stark, it is quite possible that the efforts of the colonials would have failed.

General John Stark, is quite likely the most famous New Hampshire military hero and, quite likely, the Revolutionary war hero that we know the least about. This despite the fact that he was an officer at the battle of Bunker Hill, The Siege of Boston, the Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton in addition to his courageous leadership in Bennington. In addition to being a patriot, Stark was a farmer and woodsman first and foremost and a very private man.

Biographers of George Washington often compare him to Cincinnatus the Roman farmer patriot famed for his selfless service and his persistent desire to return to his farm and private life, but many historians concur that Stark was a far more appropriate comparison.

In addition to his service to the Revolution, John Stark was also second in command during the French and Indian War to Robert Rogers of Roger’s Rangers. The legendary warrior who founded what today we know as the Army Rangers. Rogers was famed as an Indian fighter. In fact to the Iroquois people and the Abenaki both he was referred to as “The White Devil”

So by the time that the Stark family settled in Manchester the attack on the Pemigewasset village and the renaming of the river had already happened and by the time John Stark was born the poetic name of the Asquamchumaukeee River had already been changed to the rather pedestrian Baker River.

Along this river on April 28, 1752, John Stark and Amos Eastman were captured by Abenaki warriors and taken to Saint-François-du-Lac, Quebec, near Montreal. John Stark's brother William Stark escaped, and David Stinson was killed during the ambush.

In 1759 Lord Jeffrey Amherst, the man for whom Amherst College was named, issued an order for Robert Rogers Rangers to attack St Francis and destroy the village. This was not the first attack that Amherst had ordered on the village of St. Francis. Amherst was one of the first British commanders to employ smallpox infected blankets against native people.

Stark refused to participate - though he was second in command in the Rangers. He told Rogers that the Abenaki had shown him great kindness and he would not make war on his adopted village.

His life would leave an indelible mark on New Hampshire and the country.

Indian Village Attack Site

Indian plaque just off Route 3 heading into downtown Plymouth it reads:

ASQUAMCHUMAUKE WAS THE NAME OF THE BAKER RIVER IN THE LANGUAGE OF THE PEMIGEWASSET INDIANS MEANING "CROOKED WATER FROM HIGH PLACES"

HERE WAS THE SITE OF THEIR INDIAN VILLAGE ON THESE MEADOWS THEY CULTIVATED CORN IN THE SANDY BANKS OF THE RIVER THEY STORED THEIR FURS.

IN MARCH, 1712, LIEUTENANT THOMAS BAKER AND THIRTY SCOUTS DESTROYED THE VILLAGE AND KILLED MANY INDIANS INCLUDING THE CHIEF WATERNUMMUS

ERECTED BY THE ASQUAMCHUMAUKE CHAPTER DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN 1940

Baker bio

https://www.mount-royal.ca/heritage/getperson.php?personID=I5147&tree=godbout

Plymouth Town Hall: Constructed in 1889, this building served as the Grafton County Courthouse and the former district court for many years. Now it houses the town’s public offices. The cannon in front of the Town Hall is believed to have been used by the British in the Battle of Bennington on August 16, 1777 and was captured by General John Stark.

Paul Pouliot

“Cowass” features Paul and Denise Pouliot of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People, describing and singing “Cowass Honor Song.”

This episode features Paul Pouliot of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People telling the story of maple syrup. Learn about Gluskabe, the Alnombak, and why maple syrup is made the way it is today.

https://indigenousnh.com/2018/11/23/indigenous-nh-101-maple-syrup/

“Cowass means Place of the White Pines and we are the People of the White Pines.”

**The route referred to was known as the Asquamchumaukee Trail. It led from Meredith Neck to Squam Lake to Little Squam Lake to Plymouth, then along the Baker (Asquamchumaukee) River to Wentworth and Glencliff, then through the Oliverian Notch to Haverhill, where it crossed the Connecticut River to end in Newbury, VT. This route was used many times by raiding parties from Canada, and earlier, from Mohawk territory.

|

| An Arabian Dream in a Field of Lupine |

John Stark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

For other people named John Stark, see John Stark (disambiguation).

John Stark

"Live free or die: Death is not the worst of evils."

Nickname(s)

The Hero of Bennington

Born

August 28, 1728

Londonderry, Province of New Hampshire

Died

May 8, 1822 (aged 93)

Manchester, New Hampshire, United States

Place of burial

Stark Cemetery, Manchester (

Coordinates:

)

Allegiance

Service/branch

Years of service

1775–1783

Rank

Unit

Roger's Rangers

Continental Army

Commands held

Northern Department

New Hampshire Militia

1st New Hampshire Regiment

Battles/wars

French and Indian War

Battle on Snowshoes (1757)

Battle of Carillon

American Revolutionary War

Siege of Boston

Battle of Bunker Hill

Invasion of Canada (1775)

Battle of Trenton

Battle of Princeton

Battle of Bennington

John Stark (August 28, 1728 – May 8, 1822) was a New Hampshire native who served as an officer in the British Army during the French and Indian war and a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. He became widely known as the "Hero of Bennington" for his exemplary service at the Battle of Bennington in 1777.

External links

Early life[edit]

John Stark.

John Stark was born in Londonderry, New Hampshire[1] (at a site that is now in Derry) in 1728. His father, Archibald Stark (1693-1758) [2] was born in Glasgow, Scotland, to parents who were from Wiltshire, England;[3] Stark's father met his future wife when he moved to Londonderry in Ireland.[4] When Stark was eight years old, his family moved to Derryfield (now Manchester, New Hampshire), where he lived for the rest of his life. Stark married Elizabeth "Molly" Page, with whom he had 11 children including his eldest son Caleb Stark.

On April 28, 1752, while on a hunting and trapping trip along the Baker River, a tributary of the Pemigewasset River, he was captured by Abenaki warriors and brought back to Canada but not before warning his brother William to paddle away in his canoe, though David Stinson was killed. While a prisoner of the Abenaki, he and his fellow prisoner Amos Eastman were made to run a gauntlet of warriors armed with sticks. Stark grabbed the stick from the first warrior's hands and proceeded to attack him, taking the rest of the warriors by surprise. The chief was so impressed by this heroic act that Stark was adopted into the tribe, where he spent the winter.[5]

The following spring a government agent sent from the Province of Massachusetts Bay to work on the exchange of prisoners paid his ransom of $103 Spanish dollars and $60 for Amos Eastman. Stark and Eastman then returned to New Hampshire safely.

French and Indian War[edit]

Further information: Great Britain in the Seven Years War

Stark served as a second lieutenant under Major Robert Rogers during the French and Indian War. His brother William Stark served beside him in Rogers' Rangers. As a member of the daring Rogers' Rangers, Stark gained valuable combat experience and a detailed knowledge of the northern frontier of the American colonies. While serving with the rangers in 1757, Stark went on a scouting mission toward Fort Carillon in which the rangers were ambushed.

General Jeffery Amherst, in 1759 ordered Rogers' Rangers to journey from Lake George to the Abenaki village of St. Francis, deep in Quebec. The Rangers went north and attacked the Indian town. Stark, Rogers' second-in-command of all ranger companies, refused to accompany the attacking force out of respect for his Indian foster-parents residing there. He returned to New Hampshire to his wife, whom he had married the previous year.

At the end of the war, Stark retired as a captain and returned to Derryfield, New Hampshire.

American Revolution[edit]

Replica of the Green Mountain Boys flag in John Stark's collection.

Bunker Hill[edit]

The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, signaled the start of the American Revolutionary War, and Stark returned to military service. On April 23, 1775, Stark accepted a Colonelcy in the New Hampshire Militia and was given command of the 1st New Hampshire Regiment and James Reed of the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, also outside of Boston. As soon as Stark could muster his men, he ferried and marched them south to Boston to support the blockaded rebels there. He made his headquarters in the confiscated Isaac Royall House in Medford, Massachusetts.

On June 16, the rebels, fearing a preemptive British attack on their positions in Cambridge and Roxbury, decided to take and hold Breed's Hill, a high point on the Charlestown peninsula near Boston. On the night of the 16th, American troops moved into position on the heights and began digging entrenchments.

As dawn approached, lookouts on HMS Lively, a 20-gun sloop of war noticed the activity and the sloop opened fire on the rebels and the works in progress. This in turn drew the attention of the British admiral, who demanded to know what the Lively was shooting at. Subsequent to that, the entire British squadron opened fire. As dawn broke on June 17 the British could clearly see hastily constructed fortifications on Breed's Hill, and British Gen. Thomas Gage knew that he would have to drive the rebels out before fortifications were complete. He ordered Major General William Howe to prepare to land his troops. Thus began the Battle of Bunker Hill. American Col. William Prescott held the hill throughout the intense initial bombardment with only a few hundred American militia. Prescott knew that he was sorely outgunned and outnumbered. He sent a desperate request for reinforcements.

Stark and Reed with the New Hampshire minutemen arrived at the scene soon after Prescott's request. The Lively had begun a rain of accurate artillery fire directed at Charlestown Neck, the narrow strip of land connecting Charlestown to the rebel positions. On the Charlestown side, several companies from other regiments were milling around in disarray, afraid to march into range of the artillery fire. Stark ordered the men to stand aside and calmly marched his men to Prescott's positions without taking any casualties.

When the New Hampshire militia arrived, the grateful Colonel Prescott allowed Stark to deploy his men where he saw fit. Stark surveyed the ground and immediately saw that the British would probably try to flank the rebels by landing on the beach of the Mystic River, below and to the left of Bunker Hill. Stark led his men to the low ground between Mystic Beach and the hill and ordered them to "fortify" a two-rail fence by stuffing straw and grass between the rails. Stark also noticed an additional gap in the defense line and ordered Lieutenant Nathaniel Hutchins from his brother William's company and others to follow him down a 9-foot-high (2.7 m) bank to the edge of the Mystic River. They piled rocks across the 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) beach to form a crude defense line. After this fortification was hastily constructed, Stark deployed his men three-deep behind the wall. A large contingent of British with the Royal Welch Fusiliers in the lead advanced towards the fortifications. The Minutemen crouched and waited until the advancing British were almost on top of them, and then stood up and fired as one. They unleashed a fierce and unexpected volley directly into the faces of the fusiliers, killing 90 in the blink of an eye and breaking their advance. The fusiliers retreated in panic. A charge of British infantry was next, climbing over their dead comrades to test Stark's line. This charge too was decimated by a withering fusillade by the Minutemen. A third charge was repulsed in a similar fashion, again with heavy losses to the British. The British officers wisely withdrew their men from that landing point and decided to land elsewhere, with the support of artillery.

Later in the battle, as the rebels were forced from the hill, Stark directed the New Hampshire regiment's fire to provide cover for Colonel Prescott's retreating troops. The day's New Hampshire dead were later buried in the Salem Street Burying Ground, Medford, Massachusetts.

While the British did eventually take the hill that day, their losses were formidable, especially among the officers. After the arrival of General George Washington two weeks after the battle, the siege reached a stalemate until March the next year, when cannon seized at the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga were positioned on Dorchester Heights in a deft night manoeuvre. This placement threatened the British fleet in Boston Harbor and forced General Howe to withdraw all his forces from the Boston garrison and sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Among the notable men who served under Stark was Captain Henry Dearborn, who later became Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson. Dearborn arrived with 60 militia men from New Hampshire.[6]

Trenton and Princeton[edit]

Statue at Stark Park in Manchester, New Hampshire

As Washington prepared to go to New York in anticipation of a British attack there, he knew that he desperately needed experienced men like John Stark to command regiments in the Continental Army. George Washington immediately offered Stark a command in the Continental Army. Stark and his New Hampshire regiment agreed to attach themselves to the Continental Army. The men of the New Hampshire Line were sent as reinforcements to the Continental Army during the Invasion of Canada in the spring of 1776. After the retreat of the Continental Army from Canada, Stark and his men traveled to New Jersey to join Washington's main army. They were with Washington in the battles of Princeton and Trenton in late 1776 and early 1777.

After Trenton, Washington asked Stark to return to New Hampshire to recruit more men for the Continental Army. Stark agreed, but upon returning home, learned that while he had been fighting in New Jersey, a fellow New Hampshire Colonel named Enoch Poor had been promoted to Brigadier General in the Continental Army. In Stark's opinion, Poor had refused to march his militia regiment to Bunker Hill to join the battle, instead choosing to keep his regiment at home. Stark, an experienced woodsman and fighting commander, had been passed over for someone with no combat experience and apparently no will to fight. On March 23, 1777, Stark resigned his commission in disgust, although he pledged his future aid to New Hampshire if it should be needed.

Bennington and beyond[edit]

General Stark's statue at the Bennington Battle Monument

Four months later, his home state offered Stark a commission as brigadier general of the New Hampshire Militia. He accepted on the strict condition that he would not be answerable to Continental Army authority. Soon after receiving his commission, Stark assembled 1,492 militiamen in civilian clothes with personal firearms. He traveled to Manchester, Vermont. At this place, he was ordered by Major General Benjamin Lincoln (of the Continental Army) to reinforce Philip Schuyler's Continental army on the Hudson River. Stark refused to obey Lincoln, who was another general whom he believed was unfairly promoted over his head. Lincoln was diplomatic enough to allow him to operate independently against the rear of General John Burgoyne's British army.[7]

Burgoyne sent an expedition under Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum to capture American supplies at Bennington, Vermont. Baum commanded 374 Brunswick infantry and dismounted dragoons, 300 Indians, loyalists, and Canadians, and two 3-pound cannons manned by 30 Hessians.[8] Stark heard about the raid and marched his force to Bennington. Meanwhile, Baum received intelligence that Bennington was held by 1,800 men. On August 14, Baum asked Burgoyne for reinforcements but assured his army commander that his opponents would not give him much trouble.[9] The Brunswick officer then fortified his position and waited for Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann's 642 soldiers and two 6-pound cannons to reach him. Colonel Seth Warner also set out with his 350 men to reinforce Stark.[10]

After waiting out a day of rain, at 3:00 PM on the 16th Stark sent 200 militia to the right, 300 men to the left, 200 troops against a position held by Tories, and 100 men on a feint against Baum's main redoubt. In the face of these attacks, the Indians, loyalists, and Canadians fled, leaving Baum stranded in his main position. As his envelopment took effect, Stark led his remaining 1,200 troops against Baum, saying, "We'll beat them before night or Molly Stark's a widow." After an ammunition wagon exploded, Baum's men tried to hack their way out of the trap with their dragoon sabers. Baum was fatally hit and his men gave up around 5:00 PM.[11] With Stark's men somewhat scattered by their victory, Breymann's column appeared on the scene. At this moment Colonel Seth Warner's 350 Green Mountain Boys arrived to confront Breymann's men. Between Stark and Warner, the Germans were stopped and then forced to withdraw. The New Hampshire and Vermont soldiers severely mauled Breymann's command but the German officer managed to get away with about two-thirds of his force.[12] Historian Mark M. Boatner wrote,

As a commander of New England militia Stark had one rare and priceless quality: he knew the limitations of his men. They were innocent of military training, undisciplined, and unenthusiastic about getting shot. With these men he killed over 200 of Europe's vaunted regulars with a loss of 14 Americans killed.[13]

Another version has Stark rallying his troops with the cry, "There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!"

Stark's action contributed to the surrender of Burgoyne's northern army after the Battles of Saratoga by raising American morale, by keeping the British from getting supplies, and by subtracting several hundred men from the enemy order of battle. Stark reported 14 killed and 42 wounded. Of Baum's 374 professional soldiers, only nine men escaped. For this feat Stark won his coveted promotion to brigadier general in the Continental Army on October 4, 1777.[14]

Saratoga is seen as the turning point in the Revolutionary War, as it was the first major defeat of a British general and it convinced the French that the Americans were worthy of military aid. After the Battle of Freeman's Farm Gen. Stark's brigade moved into a position at Stark's Knob cutting off Burgoyne's retreat to Lake George and Lake Champlain.

John Stark sat as a judge in the court martial that in September 1780 found British Major John André guilty of spying and in helping in the conspiracy of Benedict Arnold to surrender West Point to the British.

He was the commander of the Northern Department three times between 1778 and 1781 along with commanding a brigade at the Battle of Springfield in June 1780.

Later years[edit]

Gravesite in Stark Park, Manchester, New Hampshire

After serving with distinction throughout the rest of the war, Stark retired to his farm in Derryfield, renamed Manchester in 1810, where he died on May 8, 1822 at the age of 93.

It has been said[by whom?] that of all the Revolutionary War generals, Stark was the only true Cincinnatus because he truly retired from public life at the end of the war. In 1809, a group of Bennington veterans gathered to commemorate the battle. General Stark, then aged 81, was not well enough to travel, but he sent a letter to his comrades, which closed "Live free or die: Death is not the worst of evils." The motto Live Free or Die became the New Hampshire state motto in 1945. Stark and the Battle of Bennington were later commemorated with the 306-foot (93 m) tall Bennington Battle Monument and a statue of Stark in Bennington, Vermont.

Historic sites[edit]

There is a New Hampshire historical marker (number 48) near John Stark's birthplace on the east side of New Hampshire Route 28 (Rockingham Road) in Derry, New Hampshire, just south of the intersection of Lawrence Road.[15] There is a second stone marker at the actual homestead location.

Stark's childhood home is located at 2000 Elm Street in Manchester, New Hampshire. The home was built in 1736 by John's father Archibald. The building is now owned by the Molly Stark Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The property, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is open by appointment only. Manchester's Stark Park, also a listed property, is home to his grave and is named in his honor. There is a bronze statue of General Stark in front of the New Hampshire Statehouse in Concord; it was dedicated in 1890. New Castle's Fort Stark was renamed for the General in 1900. It was one of seven forts built in the area to protect the nearby city of Portsmouth. The historic site is placed on a peninsula known as Jerry's point (or Jaffrey's Point) on the southeast side of the island.[16]

See also[edit]

Detailed information on John Stark is not easy to find. Please add references and primary resources to this section, noting where the resources can be found.

Reminiscences of the French War; containing Rogers' Expeditions with the New-England Rangers under his command, as published in London in 1765; with notes and illustrations. To which is added an account of the life and military services of Maj. Gen. John Stark; with notices and anecdotes of other officers distinguished in the French and Revolutionary wars.

Concord, N.H.: Published by Luther Roby, 1831. A copy can be found in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Reminiscences of the French War with Robert Rogers' journal and a memoir of General Stark. Freedom, N.H.: Freedom Historical Society, 1988. OCLC number: ocm18143265. A copy can be found in the Boston Public Library.

Memoir and official correspondence of Gen. John Stark, with notices of several other officers of the Revolution. Also a biography of Capt. Phine[h]as Stevens and of Col. Robert Rogers, with an account of his services in America during the "Seven Years' War." With a new introd. and pref. by George Athan Billias; by Stark, Caleb, 1804–1864. pub. Boston, Gregg Press, 1972 [c1860].

The Papers of John Stark, New Hampshire Historical Society, 30 Park Street, Concord, New Hampshire. An unpublished guide to the collection is available at the Society's library.

Secondary references[edit]

Gen. John Stark's home farm: a paper read before the Manchester Historic Association October 7, 1903; by Roland Rowell. A copy can be found in the Boston Public Library.

Major General John Stark, hero of Bunker Hill and Bennington, 1728–1822; by Leon W. Anderson. [n.p.] Evans Print. Co., c1972. OCLC 00709356

. A copy can be found in the Boston Public Library.

Polhemus, Richard V.; Polhemus, John F. (2014). Stark: The Life and Wars of John Stark, French and Indian War Ranger, Revolutionary War General. Black Dome Press. ISBN 978-1883789749.

Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. Oxford University Press, 2009.

John Stark, Freedom Fighter; by Robert P. Richmond. Waterbury, Conn.: Dale Books, 1976. (Juvenile literature). A copy can be found in the Boston Public Library.

Patriots: the men who started the American Revolution; by A.J. Langguth. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0-671-67562-1.

A New Age Now Begins: A People's History of the American Revolution; by Page Smith. Vols I and II of VIII. (Note: vol. II contains the index for both vol. I and vol. II). ISBN 0-07-059097-4.

Statue of John Stark at the U.S. Capitol

The Adventures of Brigadier General John Stark

, an historical humor web comic by Eric Burns, told from the point of view of a similar statue at the Bennington Battle Monument

Statue of John Stark at New Hampshire State House Complex

Dr. Lisa Doner

The Baker River, or Asquamchumauke[1] (an Abenaki word meaning "salmon spawning place"),[2] is a 36.4-mile-long (58.6 km)[3] river in the White Mountains region of New Hampshire in the United States. It rises on the south side of Mount Moosilauke and runs south and east to empty into the Pemigewasset River in Plymouth. The river traverses the towns of Warren, Wentworth, and Rumney. It is part of the Merrimack River watershed.

The Baker River's name recalls Lt. Thomas Baker (1682–1753), whose company of 34 scouts from Northampton, Massachusetts, passed down the river's valley in 1712 and destroyed a Pemigewasset Indian village. Along this river on April 28, 1752, John Stark and Amos Eastman were captured by Abenaki warriors and taken to Saint-François-du-Lac, Quebec, near Montreal. John Stark's brother William Stark escaped, and David Stinson was killed during the ambush.

On the 1835 Thomas Bradford map of New Hampshire, the river is shown as "Bakers" River, originating on "Mooshillock Mtn."

Major tributaries

Asquamchumaukee - Place of Mountain Waters

http://bit.ly/BakerRiverValley

A photographic ramble through the Baker River Valley of New Hampshire

Limited edition signed: $149.00

http://bit.ly/BakerRiverValley

Widget

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=1366610423&asins=1366610423&linkId=89dc2d4d025dcebd5d9900cbf90e32d1&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Small Hardcover $ 59.35

http://bit.ly/AsquamSMHard

Hardcover: 42 pages

Publisher: Blurb (2014)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1320165141

ISBN-13: 978-1320165143

Package Dimensions: 10.2 x 8.5 x 0.6 inches

Average Customer Review: Be the first to review this item

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #7,196,763 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

#94217 in Books > Arts & Photography > Photography & Video

Widget

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=1320165141&asins=1320165141&linkId=68119fcd975d31c5aa7fb6e828f36648&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Paperback: $39.58

http://bit.ly/AsquamPaper

Paperback: 42 pages

Publisher: Blurb (2014)

ISBN-10: 1320165168

ISBN-13: 978-1320165167

ASIN: B00Z8FX5JU

Package Dimensions: 10.2 x 8.5 x 0.3 inches

Average Customer Review: Be the first to review this item

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #4,655,786 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

#74185 in Books > Arts & Photography > Photography & Video

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=B00Z8FX5JU&asins=B00Z8FX5JU&linkId=cf832ea06e38f4c2b8fd5c95985c04a6&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Asquamchumaukee

Place of Mountain Waters

A photographic ramble through the Baker River Valley of New Hampshire

This book and the images from it are available in a number of different formats including a large landscape hardcover, signed and numbered, limited edition art book; an open edition in hardcover, softcover and eBook formats as well as other related products including calendars, clocks, mugs, cards, posters and prints.

Signed, Numbered Limited Edition, Large Format $165.00

This book requires the artist to sign and number the books, it can ONLY be ordered directly from me at this secure address:

http://bit.ly/OrderAsquam

Open Edition (unsigned) - Large Format $98.76

Available through Amazon.com

Large Landscape Hardcover 13” x 11”

42 Pages printed on standard paper

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo3

Open Edition Small Hardcover (unsigned) - 8"x10" Format $59.35

Available through Amazon.com

Standard Landscape Hardcover 8” x 10”

42 Pages printed on standard paper

Hardcover with Dust Jacket:

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo5

Softcover "Keepsake Version" 8"x10": $39.58

Plus shipping & handling

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo6

eBook from Blurb

42 Pages

$4.99

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo7

Detailed information about Calendars, cards, clocks and other gifts can be found here.

http://bit.ly/BakerValleyGifts

Asquamchumaukee Facebook Page

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Asquamchumaukee-Baker-River-Valley/189924584514401?ref=hl

http://bit.ly/Asquam_FB

Images from the Asquamchumaukee

Affordable open edition prints

https://fineartamerica.com/profiles/wayne-king?tab=artworkgalleries&artworkgalleryid=461098

A photographic ramble through the Baker River Valley of New Hampshire

Limited edition signed: $149.00

http://bit.ly/BakerRiverValley

Widget

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=1366610423&asins=1366610423&linkId=89dc2d4d025dcebd5d9900cbf90e32d1&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Small Hardcover $ 59.35

http://bit.ly/AsquamSMHard

Hardcover: 42 pages

Publisher: Blurb (2014)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1320165141

ISBN-13: 978-1320165143

Package Dimensions: 10.2 x 8.5 x 0.6 inches

Average Customer Review: Be the first to review this item

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #7,196,763 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

#94217 in Books > Arts & Photography > Photography & Video

Widget

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=1320165141&asins=1320165141&linkId=68119fcd975d31c5aa7fb6e828f36648&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Paperback: $39.58

http://bit.ly/AsquamPaper

Paperback: 42 pages

Publisher: Blurb (2014)

ISBN-10: 1320165168

ISBN-13: 978-1320165167

ASIN: B00Z8FX5JU

Package Dimensions: 10.2 x 8.5 x 0.3 inches

Average Customer Review: Be the first to review this item

Amazon Best Sellers Rank: #4,655,786 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

#74185 in Books > Arts & Photography > Photography & Video

<iframe style="width:120px;height:240px;" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" scrolling="no" frameborder="0" src="//ws-na.amazon-adsystem.com/widgets/q?ServiceVersion=20070822&OneJS=1&Operation=GetAdHtml&MarketPlace=US&source=ss&ref=as_ss_li_til&ad_type=product_link&tracking_id=hearcom-20&marketplace=amazon®ion=US&placement=B00Z8FX5JU&asins=B00Z8FX5JU&linkId=cf832ea06e38f4c2b8fd5c95985c04a6&show_border=true&link_opens_in_new_window=true"></iframe>

Asquamchumaukee

Place of Mountain Waters

A photographic ramble through the Baker River Valley of New Hampshire

This book and the images from it are available in a number of different formats including a large landscape hardcover, signed and numbered, limited edition art book; an open edition in hardcover, softcover and eBook formats as well as other related products including calendars, clocks, mugs, cards, posters and prints.

Signed, Numbered Limited Edition, Large Format $165.00

This book requires the artist to sign and number the books, it can ONLY be ordered directly from me at this secure address:

http://bit.ly/OrderAsquam

Open Edition (unsigned) - Large Format $98.76

Available through Amazon.com

Large Landscape Hardcover 13” x 11”

42 Pages printed on standard paper

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo3

Open Edition Small Hardcover (unsigned) - 8"x10" Format $59.35

Available through Amazon.com

Standard Landscape Hardcover 8” x 10”

42 Pages printed on standard paper

Hardcover with Dust Jacket:

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo5

Softcover "Keepsake Version" 8"x10": $39.58

Plus shipping & handling

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo6

eBook from Blurb

42 Pages

$4.99

http://bit.ly/AsquamNo7

Detailed information about Calendars, cards, clocks and other gifts can be found here.

http://bit.ly/BakerValleyGifts

Asquamchumaukee Facebook Page

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Asquamchumaukee-Baker-River-Valley/189924584514401?ref=hl

http://bit.ly/Asquam_FB

Images from the Asquamchumaukee

Affordable open edition prints

https://fineartamerica.com/profiles/wayne-king?tab=artworkgalleries&artworkgalleryid=461098

No comments:

Post a Comment